LOUIS XIII 1610-1643

It was during the reign of Louis III, successor to Henri IV, that French design began to free itself from the influence of the Renaissance, with its constant reference to antiquity. Whereas the coffer had prevailed for centuries, furniture types were becoming more varied, with the appearance of many new styles of chairs, tables and armoires. Ornately carved elements gave way to simpler forms of decoration. Geometric shapes such as carved diamond-heads appeared, and the introduction of new woodturning techniques lead to the rise of turned legs on chairs, tables and stands. Furniture of this era tends to be large and imposing, most commonly in oak and walnut.

LOUIS XIV 1643-1715

Most of the furniture of this era was designed in the Baroque taste, modelled on the furnishings of the magnificent palace of Versailles, home of Louis XIV, the ‘Sun King’. The furniture was of a heavy, masculine style copied from the Jesuit architecture of Italy. Each piece was designed to harmonize with the room it was to go in. The Italian cassone (chest) was transformed into the commode – essentially a coffer on legs with drawers. Very heavy ornate console tables were placed beneath huge mirrors. Beds were richly draped. Sofas and chaise longues came into use.

Decorations included masks, shells, trophies of arms, animals, mythological figures and royal symbols, such as the sunburst. Gilded and painted furniture was common and Chinese lacquered panels were used. Ebenists (cabinetmakers) such as Boulle, were the most important craftsmen, producing exquisite veneers and inlays in marquetry.

REGENCE 1715-1730

Philippe d’Orleans was Regent during the minority of Louis XV from 1715 to 1723. It was during this period that the ‘Regence’ style, a transitional phase between Baroque (Louis XIV) and Rococo (Louis XV), was developed.

The most common motifs, carved or engraved in bronze, are symmetrical shells and palmettes. The era is noted for the creation of the ‘bureau plat’ (large, heavily decorated writing table), the ‘commode en tombeau’ (or bombé commode), and the ‘fauteuil canné’ (caned armchair).

An appreciation of comfort, under the reign of Louis XV, will lead to a new ‘art de vivre’.

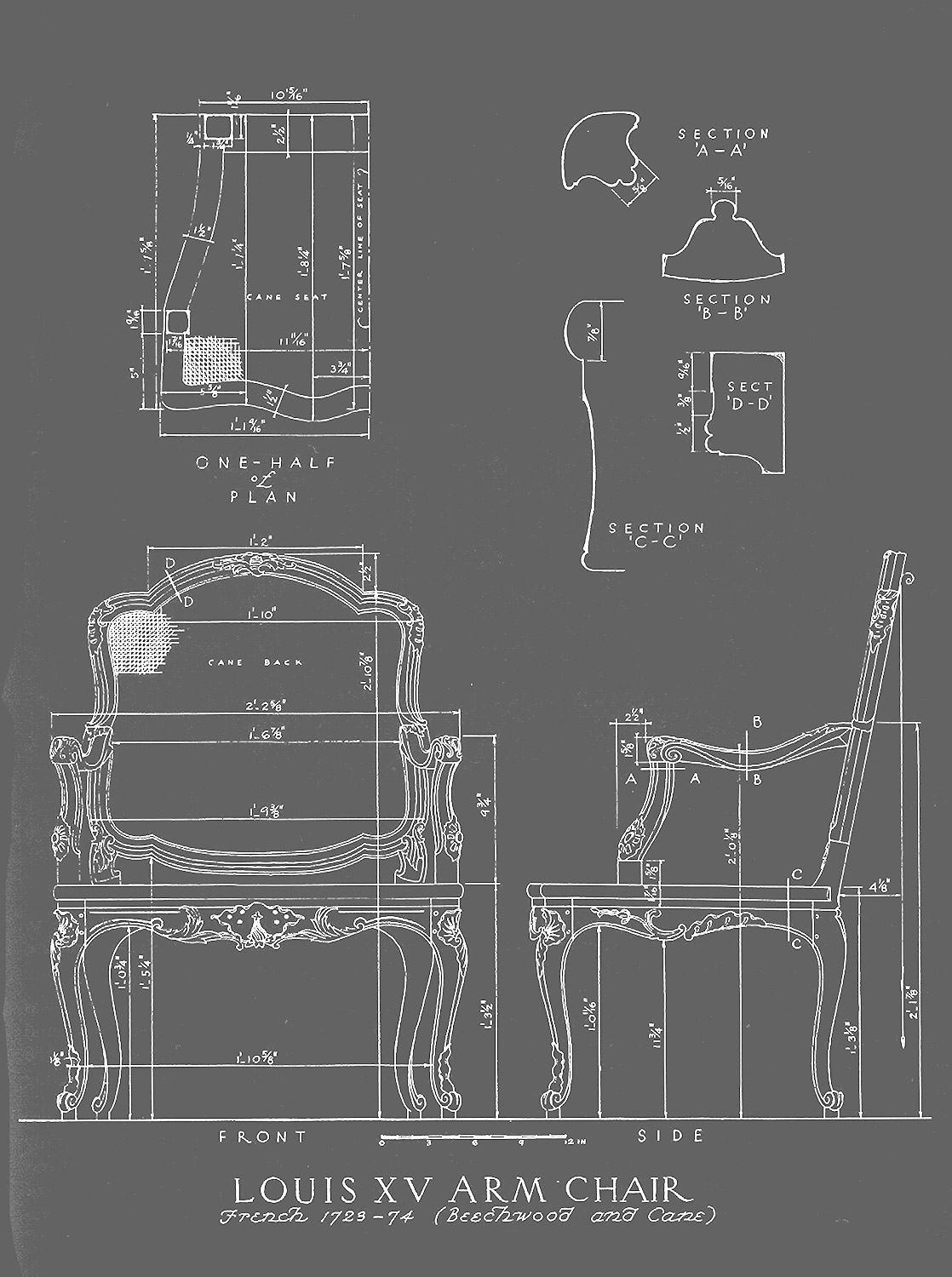

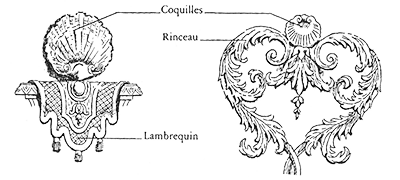

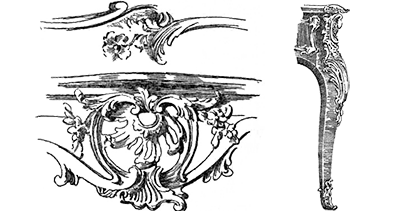

LOUIS XV 1730-1770

The changes which had begun with the ‘Regence’ were continued in Louis XV styles. The ladies at court strongly influenced the new, less formal, way of life. Small delicate pieces of furniture were designed specially for them, such as desks and dressing tables. Styles of decoration were very feminine. They included much more marquetry, and floral designs were the most popular. More furniture was painted, often depicting romantic pastoral (country) scenes. Many of the designs were in the rococo style, in which nothing is symmetrical. Most of these motifs were taken from nature, i.e; shells, flowers and foliage. ‘Ormolu’ (gilded bronze or brass ornamentation) was introduced as a luxurious form of decoration. Most tables and chairs were given cabriole legs.

Simplified rococo motifs, curves and ‘escargot’ (scroll) feet were common in country furniture of this era.

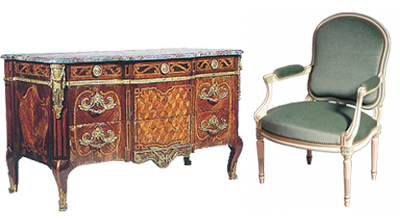

TRANSITION STYLE 1750-1775

The style known as ‘Transition’ or late Rococo, is in some ways comparable to ‘Regence’, and shows similarities to both preceding styles and those that followed. The strongest new design influence was public interest in the Roman excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum. Lines became more angular, and the Greek ‘key’ pattern was introduced. Curves were less pronounced, chair frames became thinner, and chair-backs were oval or round.

LOUIS XVI 1770-1790

The flowing curves of the Rococo disappeared, as all the classical shapes were based on straight lines. These were emphasised by straight fluting and grooving as decoration became architectural again. The ribbons and leaves of the Louis XIV style reappeared, and pine cone finials became common. Louis XVI furniture was often painted, and some was decorated with beautiful plaques (panels) of ‘Sevres’ porcelain. Elements of the classical Louis XVI style continued into the Empire period of the early 19th century. Though it should be noted that immediately following the French Revolution (1789) the comparativley plain styles of the Directoire period prevailed.

DIRECTOIRE / CONSULAT 1790-1805

The latter part of the 18th century was too troubled to favour the harmonious development of the Louis XVI style. Life for the craftsmen underwent a radical change as their traditional market, the aristocracy, disappeared. Under the Directoire, the only stable government of the period, simplification was the order of the day, reflecting the revolutionary ideals of the nation and problems in obtaining some of the exotic materials on which the elaborate craftsmanship of the preceding decades had partly depended. Types of furniture were fewer, and the Neoclassicism of the Louis XVI era was simplified into a fashion which became known as ‘Etruscan’, and more Roman than Greek. Lozenges were a much-used motif under the Directoire.

Yet the luxury workshops and manufactories of France were soon again to find new vigour, inspired by central patronage. Under the Consulat, the decorative arts were once again seen as a central expression of national prestige. Specific influences affected style and design; Napoleon’s military success in Egypt was followed by the incorporation of Egyptian motifs into a broadly neoclassical design repertory. This particular style is often called ‘Retour d’Egypte’. Features common to furniture of the Consulat period are pilasters, Egyptian and Greek figures, mahogany veneers, and lions’ heads and paws.

EMPIRE 1800-1820

This was the last style to be created entirely by the French, at the command of Napoleon I who was Emperor from 1802-1815. It was a classical style copied accurately from the imperial designs of Ancient Greece, Rome, and Egypt. This was in contrast to the Baroque classical styles which had been freely adapted from those of Ancient Rome, and elaborated until they bore little resemblance to the original.

Empire designs were rectilinear (in straight lines) and the huge rectangular pieces of furniture had architectural proportions. The large flat surfaces were covered with great sheets of veneer, usually of mahogany, rosewood, or ebony. They were decorated with flat pieces of ormolu (gilded bronze or brass ornamentation), with very little carving. Designs included Egyptian and Greek figures, palmettes, crowns, eagles, bees (Napoleon’s emblem), swans, lions, Sphinxes and other mythical animals.

RESTAURATION 1815-1830

Although the Empire style was specifically associated with Napoleon and was spread across Europe by his conquests, it did persist in France during the years of Restauration. Generally, however, the strict neoclassical forms became more relaxed with an obvious regard for comfort, and taste became more eclectic with the emergence of the so-called ‘style duchesse de Berry’, which utilised light woods inlaid with darker ones. (This particular style is also known as ‘Charles X’.) With mahogany becoming rare, craftsmen of the Restauration period generally used lighter woods, and the taste for highly ornate ormolu, such as that of pure Empire style, diminished.

LOUIS PHILIPPE 1830-1848

As the neoclassical legacy of the Empire began to weaken in the 1830’s the influence of a burgeoning middle-class began to make itself felt. In terms of taste, this was translated into a trend toward eclecticism, and designers and cabinetmakers began to borrow features from every style from the Renaissance onwards. It was during these years that mechanical methods of manufacture were being introduced, many of which originated in France. The furniture made under Louis Philippe’s reign is generally simple, robust, practical and comfortable. While being comparatively ‘mass-produced’ and less refined than that of previous eras, it is still furniture of very high quality.

NAPOLEON III (SECOND EMPIRE) 1855-1880

The dominant trend in taste of the Second Empire was not just middle-class and eclectic, it was positively predatory with regard to the past glories of French design. Upholsterers often took over the role of coordinating whole interiors, combining pieces incorporating features borrowed from every style, and numerous forms of heavily padded furniture appeared. Upholstered armchairs and settees were grouped together to promote intimate conversation, and curtains, cushions and braids began to rule the decor. In furniture, popular taste returned to darker woods and ‘ebonising’ or ‘japaning’ (staining or laquering wood to appear black) reappeared. Among the pastiche of styles, rococo enjoyed some popularity among wealthier patrons, but it was Louis XVI style which dominated by the end of Napoleon III’s reign. Many of these pieces were of high quality, especially those bought by the prosperous Parisian ‘bourgeoisie’ to furnish their apartments. Cabinets, commodes and desks in the grand manner of Boulle and similar renowned craftsmen of the 18th century became a feature of fashionable salons, though such pieces tended to lack the finesse of the original.